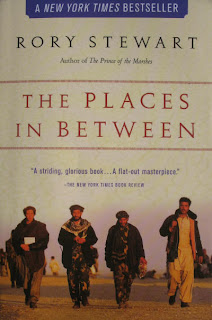

by Rory Stewart

by Rory StewartSometimes a book is a good read because the author has an incredible imagination and spins a story that draws you in and keeps you captive. Other times, a book is a good read because the story it tells is true. It opens your eyes to a new and different world. The Places In Between is such a book.

Imagine walking in the dead of winter from Herat to Kabul in Afghanistan. As it turns out, there’s more than one route. One is longer and circumvents the mountains. The second is more direct, but requires traversing the mountains, climbing over passes that reach 13,000 feet elevation.

Imagine taking this trek and surviving and not getting frostbite. Advice from the Security Service (a scary duo who interviewed the author at the onset) is simply put:

You are the first tourist in Afghanistan. It is mid-winter—there are three meters of snow on the high passes, there are wolves, and this is a war. You will die, I can guarantee. Do you want to die?Aah, but Rory Stewart is not your run-of-the-mill Scotsman. Indeed, he is used to living and traveling all over the world, working in diplomatic positions for the British Empire for much of his career. He is an Eton and Oxford-educated prodigal son, a historian in the most all-encompassing sense of the word. So, it is like a treasure find to read Rory Stewart’s account.

Not only does he describe what he is seeing, putting the people he meets in context of the land and the culture, but in an historical context as well. And sometimes, we discover, that not much as changed in a thousand years. The places that Rory Stewart visits—the places in between—are hidden from the world. No one covers them in the mainstream media, the newspapers, or journals. If not for Mr. Stewart, these places would not exist to us.

In addition to surviving the elements, Rory Stewart must also deal with a shifting political climate, where even the locals are not sure who their friends and enemies really are.

It is January, 2002, and the “coalition invasion” has just unseated the Taliban. Mr. Stewart gets unasked-for armed escorts and letters of introduction. The escorts are sometimes helpful and sometimes a hindrance. The letters work mostly for the next village alone, and from each village he must obtain letters or escorts anew. Many village leaders are wealthy within their own culture, but not all are literate. Rory Stewart’s language skills, people skills, and raw confidence see him through some tense situations.

Along the way, he acquires and then befriends a worn-out Mastiff dog who becomes his traveling companion and probably saves Rory’s life in a Jack London-type survival vignette.

And through this whole saga, Rory Stewart is carefully neutral on politics, carefully pragmatic I would say. His most political observation is

Most people in this area had not heard of Britain, though they had heard of America. Some had even heard of the World Trade Center, but they had no real concept of what it had been or why the coalition had bombed Afghanistan.His agenda is historical from the beginning and he continues that work even today, heading a foundation that helps save traditional Afghan arts and architecture, buildings, artifacts, and crafts in Kabul and throughout Afghanistan. The Turquoise Mountain area, one of the place-gems he happened upon in his trek, is the source of his foundation’s name. Rory Stewart currently lives in Kabul.